- Previous

- Share

Dwelling Utilisation & the Housing Shortage

The housing shortage is a pressing issue that’s affecting many communities around Australia, especially in Perth, Western Australia which is exhibiting one of the lowest vacancy rates of the nation’s capital cities and some of the fastest increase in rental prices, having risen 13.2% in the year to May 2023 according to Corelogic.

What Led to The Perth Housing Shortage:

First and foremost, there has been a lack of stock additions or new supply to the market as demand recovered. The ramifications of historically low dwelling completions over the past two years have been far-reaching, leading to increased social housing applications, homelessness, rising house prices, strong competition for rental accommodation and escalating rental prices, and potentially hindering growth in skilled migration as the lack of accommodation options and affordability discouraged migrants.

This low dwelling completions situation was driven by several factors including,

- a relatively weak residential market in the years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic which had discouraged housing investment,

- the pandemic containment measures and its associated supply chain disruptions, which included the reduced global labour mobility,

- increased investment spending and economic activity which absorbed labour supply,

- rising labour and material prices, which was in part a side effect of the global pandemic response,

- residential building stimulus which intensified already constrained construction sector capacity,

- changes to residential tenancy regulations and moratoriums which supressed investor sentiment.

In addition to low dwelling completions, persistent population growth together with changing household dynamics – changes to dwelling choice, housing habits and household formation caused by the pandemic also added pressure on the existing housing stock, as demand for lower density exacerbating the shortage.

Dwellings supply is notoriously inelastic, and building can be and extended process so there are no quick fixes to correcting a housing shortage, particularly when building industry capacity remains constrained. To alleviate it, there must be a short to medium term change to the way current dwellings are being utilised.

The Efficient Utilisation of Existing Dwellings:

To combat housing shortage or alleviate its most severe consequences, a potential solution lies in the efficient use of existing dwellings.

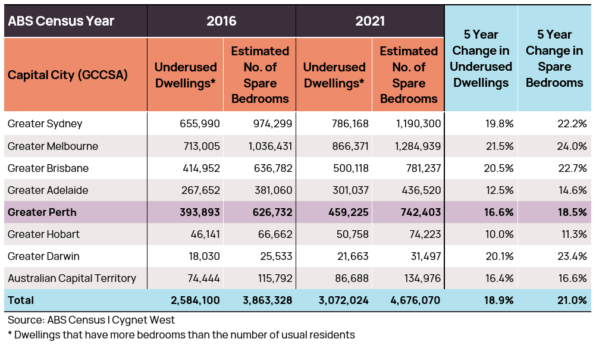

To better understand housing trends in the 5 years to 2021 and where efficiencies could be improved, Cygnet West analysed the ABS Census data on dwelling characteristics. One notable aspect that stood out was the perceived underutilisation of bedrooms in Australia’s housing stock. We kept the approach simple and defined underutilisation as being a dwelling with more bedroom than the number of usual residents e.g., a two-bedroom dwelling with only one person as usual resident or a four-bedroom dwelling with less than three usual residents.

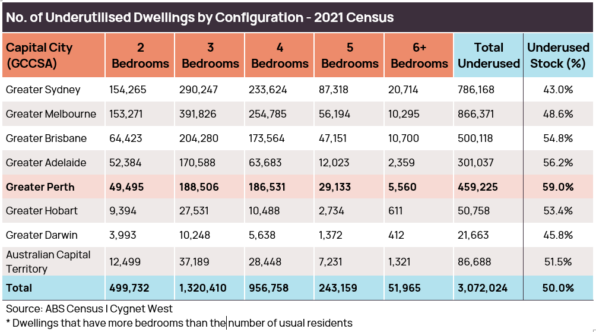

The analysis found that between 2016 and 2021 the volume of dwellings that are considered underutilised increased from 47.5% to 50% or 3,072,024 dwellings out of the 6,147,595 of measured stock (measured stock being private dwellings that had the bedroom configuration as well as the number of usual residents, there were 839,969 dwellings that were ‘not applicable’ that are vacant or for other reasons did not register a bedroom count and/or number of usual occupants).

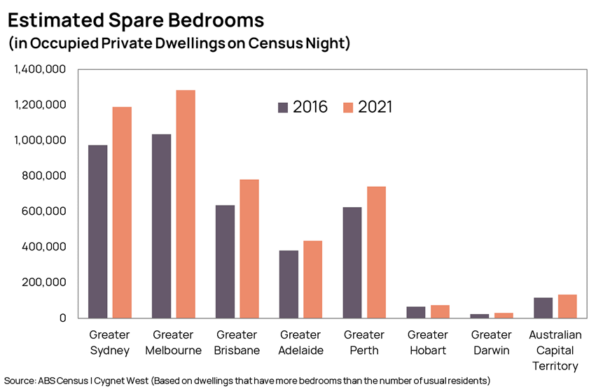

Based on the 3,072,024 dwellings considered underutilised, we estimated the total number of potential spare bedrooms that existed on the day of the Census in 2021. We found that there were at least 4,676,070 bedrooms within Australia’s existing private housing stock which were either empty or potentially being used for purposes other than a bedroom, this was an increase of 21.0% in 5 years.

We suggest that there is ‘at least’ this much because our methodology maybe considered conservative. Other similar research undertaken by the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) based on ABS survey of Income and Housing’s Housing and Occupancy Costs have indicated there could have been 13 million unused bedrooms in Australia in 2019-20.

In Greater Perth, the analysis found that 459,225 dwellings measured were underutilised, and increase of 16.6% in five years. The potential number of spare bedrooms amounted to 742,403, which was an increase of 18.5% over five years.

What was also interesting for Greater Perth was that the analysis revealed Perth had the highest underutilisation amongst Australia capital cities, with 59% of dwellings underutilised this was up from 57.1% in 2016. The city with the highest utilisation was Sydney at 43% of dwellings underutilised, but this was still higher than the 40.4% measured in 2016.

The analysis also confirmed the proportion of underutilised dwellings generally increased alongside the increase in bedrooms reported. There are several underlying reasons for this. One of which is the well-publicised empty nests dilemma in established localities. This is where adult children have left the family home and parents remain in occupation, unwilling to downsize or relocate due to factors that include, emotional attachment, relocation costs, accessibility and convenience, familiarity of local surroundings and social ties.

However, there are other factor including larger detached dwellings in more affluent localities with spare bedrooms used for home offices, gyms, utilities rooms and guest rooms etc. There also young households in the family building stage with spare bedrooms for future family expansion.

The pandemic risks and changes to work arrangements did drive people to the suburbs in search of more space and spare bedrooms for home offices, which probably also contributed to the increase in underutilisation between 2016 and 2021 resulting in the average number of people per household to fall from 2.6 to 2.5. On the surface this slight drop in density may look insignificant, but when factored or multiplied by the total number of private dwellings in Australia it amounts to almost 1 million people that could be housed at the high density across Australia. Notably, this phenomenon did appear to have had much impact on Perth’s household density, it remained unchanged between the two censuses at 2.6 person per household.

Conclusion

What this utilisation analysis suggests there is scope to significantly improve or optimise the use of our current housing stock, which to a large degree is underutilised. By encouraging homeowners to utilise spare bedrooms, the existing housing stock can effectively accommodate more individuals and families, effectively expanding the available housing supply without requiring new construction. It is an approach that should be implemented before more drastic, and potentially counterproductive, measures such as rental caps and rental freezes are suggested or implemented.

Looking at Perth’s ‘conservative’ estimated spare bedroom inventory of 742,403 rooms and using the average 3.3 bedrooms per dwelling the denominator, the number of spare bedrooms equates to nearly 225,000 dwellings or almost 10 years of supply at 22,500 dwellings per year. Nationally, using an average 3.1 bedrooms per dwelling and 4.67 million spare bedrooms, it equates to over 1.5 million dwellings.

If some of these spare bedrooms can be freed-up to the rental market, or adult children temporarily moving back into ‘empty nest’ for an interim period, dwelling availability could be notably increased while supply catches up with demand. Helping to reducing housing cost inflation.

The financial benefits have already led to a return to house sharing and adult children -parent cohabitation, which naturally occurs during times of housing stress, but certainly more can still be done to increase the pace of change.

Increasing household density will undoubtedly bring about social challenges, however, it may also help some people learn to be more considerate and tolerant.

However, the aim of this research is not merely to encourage changes in living arrangements and house sharing; more importantly, it highlights the critical need to reform policies that impact housing demand and supply.

It is imperative that policies at all levels of government be configured to increase residential or housing mobility, allowing individuals and households to promptly relocate or ‘right-size’ as their housing needs evolve over time. The key to achieving this lies in implementing appropriate federal taxation and state stamp duty policies concerning residential dwellings and primary places of residence. These measures should ensure that selling and/or relocating does not create a financial burden but instead offers benefits to both the household and the greater community.

Furthermore, flexible housing supply policies are required at the state and local government levels to accommodate shifts in demand more readily. By reducing the financial burden of relocating and improving supply elasticity, the future utilisation of both existing and new housing stock is likely to improve.